- India

- International

Chess an escape from war for South Sudan’s players

Newest country in the world, continues to see conflict between the government and rebel groups; Chess players at Olympiad say it is everyday reality

The third round of the Tata Steel Masters was played on Monday in Wijk aan Zee. It was a peaceful day, with six games finishing in a draw, and only one decisive result. (PTI/FILE)

The third round of the Tata Steel Masters was played on Monday in Wijk aan Zee. It was a peaceful day, with six games finishing in a draw, and only one decisive result. (PTI/FILE)Deng Cypriano, South Sudan’s best-rated chess player, hates talking about war. The 40-year-old says his world goes numb when he thinks of war. The rattle of bullets pierces his ears. The rumbling military jeeps with Kalashnikovs noses pounce in front of his eyes. “An everyday reality for us, not a piece of news,” he says.

He and his team are a universe away from reality. An alternative reality almost. “And I see this beautiful world of chess, sunshine, people from all around the world and I feel positive and hopeful of humanity and peace. I hear the voice of the friends I have made, and I feel this is a beautiful world,” he says.

Almost everyone in the team has a survival story to tell, but they don’t want to relive their tales of war and famine, death and desperation. “These few days are to be celebrated, for these are some of the best days in our life, and we don’t know whether we would see days like these,” he says.

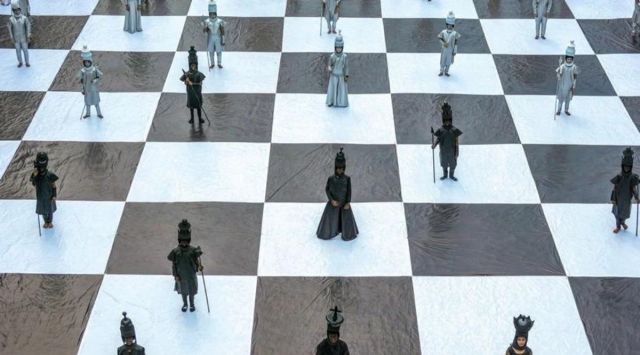

The South Sudan Vs Andorra (Europe) game during Chess Olympiad.

The South Sudan Vs Andorra (Europe) game during Chess Olympiad.

Eleven years after South Sudan was carved off Sudan, after a protracted and bloody civil war, the newest country in the world, continues to see repeated bouts of conflict between the government and rebel groups, as well as climatic shocks such as severe flooding and localised drought. According to the UN, about 8.3 million people currently require humanitarian assistance (about two-thirds of the total population), while 1.4 million children under five are acutely malnourished. The country also has the highest maternal mortality rate in the world.

A game of chess seems trivial when people are fighting for food and life every day. But the game, for Cypriano and his team, is an escape from the unimaginable realities of life. “The game we play, again it is war, but a peaceful war. It has indeed made a difference to our lives. We could see the world, represent our country, make friends and possibly show those fighting that there is a better world outside,” he says.

South Sudan Chess players during Chess Olympiad in Chennai. (Express Photo)

South Sudan Chess players during Chess Olympiad in Chennai. (Express Photo)

Several indigenous versions of the sport have been popular for centuries in South Sudan as well as other Central African countries. Cypriano and his friends picked it up in childhood and played it wherever they could squeeze in their ragged chessboard, in the corner of the house, or under the shades of a tree in the park.

“When we could not buy chess boards, we made them from wood. The rules were somewhat different, but the basics were the same,” he says.

Serious chess often began at the Munuki Chess Club in Juba, the capital city. The country’s chess fraternity flocks the club, which also organises tournaments to forge brotherhood between the diverse and often feuding ethnicities of the country. “It helps to bring people together and South Sudan really needs people to know each other, not through the tribal lens or the ethnic lens, but through capacities, capabilities and hobbies and mutual interests,”club president Jada Albert Modi had told The Juba Post.

There is no official mentoring, as the players pick and polish the game on the go. They barely fine-tune their games online, an integral part of modern-day chess development, as internet accessibility is difficult and the connection is often weak. So they often assemble in bars that have free internet access, though they can’t stay forever in the bar. Besides, it’s a difficult place for women to enter as well. “But data, online membership, all these are very expensive for us. We could manage it for a day or two, or maybe a week. But not for a month,” says Supriano.

Most of them don’t have laptops or PCs either. When the FIDE-appointed trained Vedant Goswami met them online for the first class, he was in for a shock. “They had just one laptop. During the zoom meeting, all of them, some 10-15 people including players and officials, used to squeeze into one screen in a small room. It was difficult because you don’t know who is who. It was difficult to give personalized coaching like that. We then finally arranged some more laptops for them. The internet connection would go off too,” he says.

Their game, he felt, was raw. “They were better than I had expected. There is obviously Deng who has a rating of over 2000 (2105), but most of them were raw. Every move they would look to attack and their defence was weak. So I had to prepare them on the defensive and positional front. The women’s team was quite weak, then I learnt that it was difficult for them to go out and play in bars or clubs as it is unsafe,” he explains.

The tournaments come few and far between but that has dissuaded them constantly working on their game. “We don’t have resources, but we see people in our country and we ourselves, struggle for food. So we don’t complain about resources. We just find our ways to survive and get better, to be famous and show the country and world that a sport can change lives. Chess can bring people together, it can create relationships between us, it can also bring peace to South Sudanese as well,” Cypriano says.

His eyes are bright and fresh now. They don’t show scars of war. Chess has healed some of those.