- India

- International

The need to listen to those we disagree with

Perhaps there is a lesson to be learnt from past leaders who have been successful in winning political power and ushering in democratic regimes.

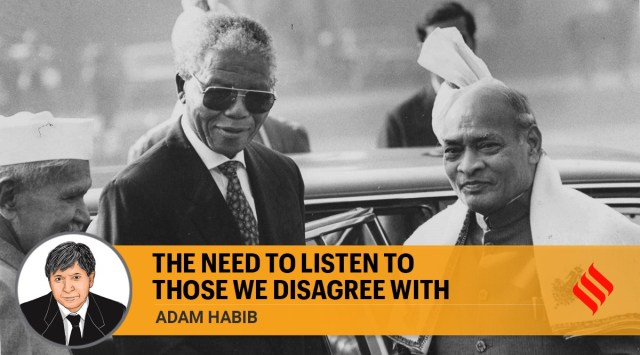

Former South African President Nelson Mandela with the President Dr. S.D. Sharma and PM P.V. Narsimha Rao at the ceremonial arrival ceremony at Rashtrapati Bhavan on 25-1-1995. (Express photo)

Former South African President Nelson Mandela with the President Dr. S.D. Sharma and PM P.V. Narsimha Rao at the ceremonial arrival ceremony at Rashtrapati Bhavan on 25-1-1995. (Express photo)We live in dangerous times. Our world today is as unequal as it was before World Wars I and II. We are increasingly becoming as socially and politically polarised as we were then. Right-wing populist and nativist parties stalk all of our lands, deepening divides among our communities both nationally and internationally. We, the progressives, rail against the forces of injustice and failures of the right-wing political elites, but have we ever pondered our own complicity in their victory? After all, it is our collective failure to win the support of the vast majority of our people that has enabled right-wing politicians to dominate the political landscape.

Perhaps there is a lesson to be learnt from past leaders who have been successful in winning political power and ushering in democratic regimes. One such example is Nelson Mandela, democratic South Africa’s first President. It is astonishing that many invoke the name of Nelson Mandela so often, and yet so few have truly understood or internalised his approach to social change. Mandela was not a distinguished thinker, and yet was one of the great leaders of the Twentieth Century. The genius of his leadership, and perhaps his greatest contribution to the intellectual agenda of transforming our world, lay in his strategic insight that if one wants to effect social change, one has to win over not only the mainstream of society but also large swathes of the social base of the opposition. This does not come without a cost. Winning over the social base of the opposition requires compromise, and results in the postponement of some social goals in favour of others. It is this that has led many young activists, no less in South Africa, to reject Mandela as an inspiration, and to politically replace him with other notable revolutionary figures like Frantz Fanon, Steve Biko and Malcolm X.

But these activists too easily dismiss the contribution of Mandela to social change. The prospect of compromise and the postponement of long cherished social goals may not be emotionally satisfying, but it is necessary for effecting long-term social change. Perhaps this may be best captured by the comparative experiences of Palestine/Israel and South Africa. Thirty years ago, social change seemed remote in both societies with each tentatively embarking on its respective path to democratisation. In one, South Africa, compromise and winning over substantive sections of the social base of the opposition was the essence of the strategic agenda of social change. On the other, in Palestine, political intransigence, no less by the Israeli establishment, enabled a historic uprising and culminated in its subsequent repression. South Africa too had this dynamic but it was contained and the stalemate was broken by the bold leadership of Mandela and his compatriots.

The net effect, 30 years later, is that the people of South Africa, despite all of the country’s failures to address inequality, corruption and even social polarisation, are in a far better position than those in Palestine. But the erosion of the South African dream suggests that another lesson is also worth reflecting on: while compromise and winning over the mainstream are important for enabling the initial breakthrough to social change, the goodwill earned can over time be lost if the social gains are frozen and progress to social justice is not continually pursued.

What then is the lesson of this experience for social change in the contemporary world? Its central lesson: antiracists, political and other activists would do well to win over and not alienate the liberal and left-of-centre social forces within society. Like Mandela and even MLK Jr. did to challenge the moral base of the oppression. This is important for building the human economies of scale required for enabling social change. It does not require abandoning social change or postponing addressing structural racism. After all, in the wake of the mobilisation around Black Lives Matter, much of the liberal intelligentsia have recognised the structural character of racism, even if they have not yet understood how to unravel it. Winning over this community is possible and is important for sustainably transforming societies. But it requires respect for civic norms like allowing for a plurality of views, avoiding the targeting and silencing of individuals, and having respectful engagements with those one is trying to convince. These are important behavioural principles not only for enabling the human economies of scale in favour of institutional change but also because they are important for protecting the essential purpose and mandate of democratic systems themselves.

This goes against the grain of an anarchic political tradition that publicly targets and humiliates those they disagree with. Social media has given this a platform and scale that has never before been available. These populist activists revel in the controversies that their incidents have generated, erroneously believing that it has put the right-wing under the microscope and has put them on the defensive. But is this even true? Are right-wing advocates not immersed in networks which would protect them even if they were guilty of social injustice? What seems more prevalent is the silencing and paralysis of liberal and even left-of-centre intellectuals, alienating them from progressive struggles that they can be won over. Moreover, these incidents have enabled opportunistic right-wing politicians to capitalise on this intolerance and win over electoral support from elements in society that would not have been possible before. These questions raise the need for urgent reflection and deliberation on the political strategy of advocates and activists of social justice, whether their current interventions are productive or counter-productive, and how to ultimately chart a path to inclusive and socially just public spaces like universities.

The writer is a Director of SOAS, University of London. He is the author of South Africa’s Suspended Revolution: Hopes and Prospects

Suraj Yengde, author of Caste Matters, curates the fortnightly ‘Dalitality’ column

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 20: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05