- India

- International

Explained: Why food inflation may ease faster than expected

International prices falling the most since Oct 2008 and a good monsoon back home make it a possibility.

The FPI hit an all-time-high of 159.7 points in March, the month that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24. (Representational)

The FPI hit an all-time-high of 159.7 points in March, the month that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24. (Representational)The global economy is “past peak inflation”, according to Elon Musk. The CEO of Tesla believes “inflation is going to drop rapidly” and prices of commodities used in the manufacture of electric vehicles “trending down in six months”.

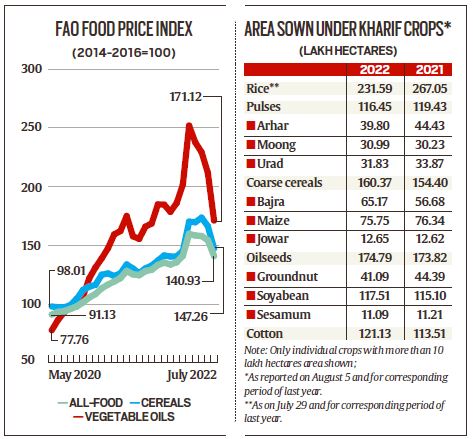

What he’s projecting is already happening in food. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index (FPI) averaged 140.9 points in July, 8.6% down from its previous month’s level and marking the steepest monthly drop since October 2008.

The FPI – a trade-weighted average of international prices of key food commodities over a base period value, taken at 100 for 2014-16 – hit an all-time-high of 159.7 points in March, the month that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24. The latest index reading is the lowest since the 135.6 points of January, before the still-ongoing war.

Between March and July, the FPI has cumulatively declined by 11.8%. This has been led by vegetable oils and cereals, whose average prices have fallen even more, by 32% and 13.4% respectively. The vegetable oil price index has been particularly volatile, soaring from a Covid demand crash-induced low of 77.8 points in May 2020 to 251.8 in March 2022, before easing to 171.1 in July (see chart).

Global factors

There were four major supply-side shock drivers of the great global food inflation from around October 2020: weather, pandemic, war and export controls.

The weather-related shocks included droughts in Ukraine (2020-21) and South America (2021-22), which especially impacted sunflower and soyabean supplies, and the March-April 2022 heat wave that devastated India’s wheat crop.

The pandemic’s supply-side impact was felt the most in Malaysia’s oil palm plantations, where harvesting of fresh fruit bunches is done mainly by migrant labourers from Indonesia and Bangladesh. As Covid-19 resulted in many of them flying back and no new work permits being issued, output from the world’s second largest palm oil producer and exporter fell.

The Russo-Ukrainian War led to supply disruptions from the two countries that, in 2019-20 (a non-war, non-drought year), accounted for 28.5% of the world’s wheat, 18.8% of corn, 34.4% of barley and 78.1% of sunflower oil exports.

Export controls were first imposed by Russia in December 2020, prompted by domestic food inflation fears arising from record hot temperatures. Shortage concerns at home triggered similar actions in palm oil by Indonesia (the world’s No. 1 producer-cum-exporter) and in wheat by India during March-May 2022.

That perfect storm, from all four shocks coming one after the other within one-and-a-half years, now seems to be receding. Its most obvious symbol is the resumption of exports from Ukraine via the Black Sea. This critical artery of the global agricultural trade was blocked after Russia launched its so-called special military operation. The UN-backed agreement for unblocking of the Black Sea trade route also provides for unimpeded shipments of Russian food and fertilisers. Russia alone is expected to export 40 million tonnes (mt) in 2022-23 (July-June), up from last year’s 33 mt.

But it isn’t Ukraine and Russia alone. Indonesia, since late-May, has lifted its ban on palm oil exports. This, even as the US, Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay are set to harvest bumper soyabean crops. Not for nothing, the price sentiment has changed. It’s most visible in edible oils, where roughly 60% of India’s annual consumption requirement is met through imports. In the last three months, the all-India modal (most-quoted) retail price has come down from Rs 175 to Rs 150 per kg for soyabean oil and from Rs 165 to Rs 142.5 for palm oil.

Not just global

Global apart, there are domestic reasons for expecting a considerable easing of food inflation.

The most important is the southwest monsoon. Cumulative rainfall during the current season from June to August 7 has been 5.7% above the historical long-term average for this period. Almost all agriculturally-significant areas – barring Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal – have received good rains so far. The prospects for the coming days seem equally encouraging, with a low-pressure area forming over northwest Bay of Bengal off the Odisha-West Bengal coasts – and another one forecast after mid-August.

Above average rainfall across the South Peninsula, Central and Northwest India has boosted acreages under most crops this kharif (monsoon) season. The exceptions, as the table shows, are rice (transplanting has taken a hit from deficient rains in the Gangetic Plain states), pulses and groundnut (their area getting diverted to cotton and soyabean that are fetching better prices).

However, rice stocks in government godowns, at 47.2 mt as of July 1, were 3.5 times the necessary “buffer” of 13.5 mt for this date. That, plus paddy being grown in the rabi (winter-spring) season as well, should make the overall rice situation manageable.

The same goes for availability of pulses. Chana (chickpea) is selling in wholesale mandis at Rs 4,400-4,600 per quintal, below its minimum support price of Rs 5,320. Government agencies are holding some 3 mt of chana and 100,000 tonnes of masur (red lentil), as against 2.2 mt and 25,000 tonnes respectively a year ago. International exportable surpluses, primarily from Canada and Australia, are also higher than last year’s by about 0.5 mt each for both pulses. In urad (black gram), too, July-end stocks in Myanmar are estimated at 0.3 mt, approximately 0.1 mt more than a year ago.

“There could be problems in arhar (pigeon-pea) because of less acreage, low government stocks (0.1 mt versus 0.4 mt last year) and no additional exportable supplies (from Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi and Myanmar). But the Narendra Modi government’s decision to allow duty-free imports of arhar, urad and masur till March 31 will keep a lid on overall prices,” said an industry source.

Trending down

All in all, there are compelling reasons – global and domestic – for food inflation in India to “trend down”, even if not “drop rapidly”. This is already being seen in edible oils. Increased soyabean and cotton production, courtesy of the monsoon, should improve availability of oil-cakes. These, along with maize, are key ingredients in animal and poultry feed. A good monsoon would also mean more fodder and water for animals, further reducing livestock input costs and inflationary pressures on milk, egg and meat.

That’s not all.

Current water levels in the country’s major reservoirs are 5.9% higher than a year back and 25.1% above their last 10 year’s average storage. If the monsoon delivers reasonably in the second half (August-September), the benefits of groundwater recharge would also flow to the rabi crop. And assuming no fresh setbacks in the Black Sea, the Reserve Bank of India’s monetary policy committee may not have to further hike interest rates.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05