- India

- International

On Gyanvapi Mosque, we are debating the wrong question

Fahad Zuberi writes: Courts cannot be acting on claims of mythology or those of medieval capture. They must leave buildings for what they are – complex sediments of history that we decided to resolve by proclaiming a break from the past and giving ourselves modern values.

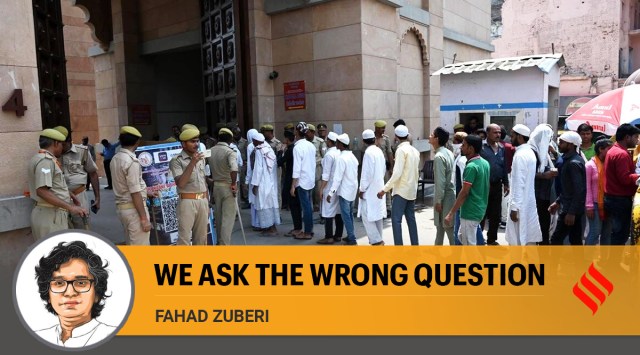

Muslims arrive to offer the Friday prayers, at Gyanvapi Masjid in Varanasi, Friday, May 13, 2022. (PTI)

Muslims arrive to offer the Friday prayers, at Gyanvapi Masjid in Varanasi, Friday, May 13, 2022. (PTI)What was being searched for (again) since the violent slogan “Ayodhya to jhanki hai, Kashi Mathura baki hai” (Ayodhya is a trailer, Varanasi and Mathura are yet to come) was exclaimed, has been found. No, not the Shivling that the petitioners of the lawsuit filed in a Varanasi civil court allege to have found in the wuzu khana of the Gyanvapi Mosque. What has been found, or rather, created, is a rupture in the wall that separates the modern constitutional democracy of India from its ancient and medieval polity — the polity characterised by expansionist warfare and legitimised by the divine instead of the values of modernity.

After the blot on our modern history called the demolition of Babri Masjid, what we see unfolding in Varanasi is another legitimisation of an apparent conflict in architectural history which, if we have not already learnt, is an exercise in violent majoritarianism. The courts that entertained the matter and then went ahead in much haste to launch an investigation into what was the building’s “true nature” are to be blamed. Had wiser discretion prevailed, the petition would not have been entertained in the first place. The question should not have been asked.

Architecture is one of the most commonly evident imprints that a civilisation leaves. While manuscripts and fragile objects remain largely inaccessible to the people — confined to the walls of museums and restoration laboratories, architecture is out for everyone to experience. People use historic buildings as inhabited spaces and visit historic sites for heritage tourism. In both cases, architecture is loaded with histories of construction, destruction, appropriation, building, re-building, and more re-building. Every building around us is a physical imprint of the times that it has lived through. It is a physical manifestation — a record — of layers of histories. And a lot of these histories are histories of conflict — a truth that cannot be escaped. To put it simply, the history of architecture is the history of politics also.

Earlier this month, the Varanasi court ordered a video survey of the Gyanvapi Mosque. The implied intention was to find out whether the fundamental claim of the petitioners that the mosque has been built by destroying or appropriating a temple holds water. While it appears fair prima facie, we — the courts, the prime time shows and the people in general — are debating the wrong question. This is not a question of secularism or that of minority rights, the question is, how will the “true nature” of our conflicted architectural sites be defined, and who has the power to define it. Reading architecture with political philosophy tells us that that depends on what values we adopt in state formation.

Historically, rulers derived legitimacy primarily in two ways. In the case of intra-state matters, the legitimacy for the king to rule came from God in the Abrahamic world and from mythology in the Pagan world. In the case of inter-state matters, kings asserted themselves through brute force and violence. The values of pre-modern state formation were divine/mythological and violent/expansionist. It was against these values that those rulers judged the function of architectural sites. The one who possessed the building by conquering the city or by becoming the king through clerical legitimacy decided what a mosque, temple or palace will be appropriated into or whether it will be allowed to exist at all. Since the French Revolution, the struggle of politics has been to find an earthly legitimacy to rule – one free from divinity, unbound to historical practices, and rejecting of violence. This has generated a long history of political thought and modern states were created on the values of modern morality – held by citizens to be self-evident truths, as proclaimed in the American Declaration of Independence.

At this juncture, it is imperative to look at The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991. Much has been written about the legality of the ongoing conflict vis-à-vis this Act. I want to shine a light on an otherwise ignored aspect of this legislation. The Act prohibited the conversion of any place of worship from its religious character as that character existed on the 15th of August, 1947. Basically, the Act said that if a site was a temple on August 15, 1947, it shall remain a temple and so on for all religious sites. We must ask ourselves: Why did an Act passed in 1991, set the date to define the status quo of religious sites to the date of India’s independence? The reason is quite profound, and for a multi-cultural and diverse society such as India, it provides a resolution to the debate around conflicted architecture.

The Act does so in the spirit of a modern nation-state. It means that since we resolved to become a modern nation on August 15, 1947, and realised it on January 26, 1950, we shall cut our ties with the systems of politics that defined our past. On the 15th of August 1947, we resolved to create a break from the past and redefine our values of political legitimacy. From that day onwards, India was to be defined by, and courts were to judge conflicts using the values of a modern state enshrined in the constitution. Not against the values of the systems of politics or mythology that existed before.

This also means that we define the “true nature” of our architectural sites against the values of modernity and not those of mythology or medieval warfare. The philosophical and practical resolution to that, as understood in the Act, is top: not entertain mythological claims to historical sites and to not investigate their archaeology for claims of possession. By ordering a survey of the Gyanvapi Mosque, the courts have done exactly the opposite.

By conducting such investigations into religious sites, the courts have, like they did in the case of Babri Masjid, legitimised the values of an anti-modern polity. They have acted against the values that they are supposed to uphold. Courts cannot be acting on claims of mythology or those of medieval capture. They must leave buildings for what they are – complex sediments of history that we decided to resolve by proclaiming a break from the past and giving ourselves modern values.

When we debate whether Gyanvapi Mosque was a temple at some point or not, and the courts order investigations into finding that out, we are all debating the wrong question. Despite precedents that speak otherwise, the higher courts must exclaim the simple yet profound answer to this question – maintain the status quo, don’t define the architecture of today by an arbitrarily chosen slice of its history. Basically, reject such petitions.

This column first appeared in the print edition on May 18, 2022 under the title ‘We ask the wrong question’. Zuberi is an independent scholar and researcher of Architecture and City Studies

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05