- India

- International

As world celebrates Nobel Peace winners, a question: Why didn’t Gandhi ever win the Prize?

How is it that Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest apostle of peace and the most inspiring symbol of non-violent struggle against oppression and discrimination in the modern era, was never honoured with the Nobel Peace Prize, either during his lifetime, or later?

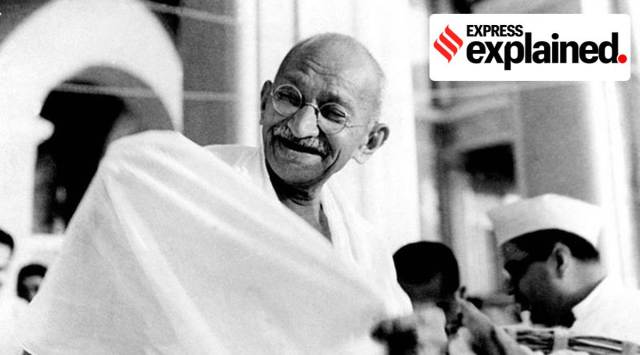

There were six Nobel Prize nominations on Gandhi's behalf, including from the 1947 and 1946 Laureates, The Quakers and Emily Greene Balch. (Express Archive)

There were six Nobel Prize nominations on Gandhi's behalf, including from the 1947 and 1946 Laureates, The Quakers and Emily Greene Balch. (Express Archive)As the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced the 2022 Peace Prize for human rights advocate Ales Bialiatski from Belarus, the Russian human rights organisation Memorial, and the Ukrainian human rights organisation Center for Civil Liberties on Friday (October 7), an old question recurred.

How is it that Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest apostle of peace and the most inspiring symbol of non-violent struggle against oppression and discrimination in the modern era, was never honoured with the Nobel Peace Prize, either during his lifetime, or later?

It is a question that the Nobel Committee has itself pondered.

The Nobel website asks: “Was the horizon of the Norwegian Nobel Committee too narrow? Were the committee members unable to appreciate the struggle for freedom among non-European peoples? Or were the Norwegian committee members perhaps afraid to make a prize award which might be detrimental to the relationship between their own country and Great Britain?”

Under the section ‘Mahatma Gandhi, the missing laureate’, the Nobel website says: “Up to 1960, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded almost exclusively to Europeans and Americans. In retrospect, the horizon of the Norwegian Nobel Committee may seem too narrow. Gandhi was very different from earlier Laureates. He was no real politician or proponent of international law, not primarily a humanitarian relief worker and not an organiser of international peace congresses. He would have belonged to a new breed of Laureates.”

Indeed, over the years, Gandhi did receive several nominations.

The Mahatma was nominated in 1937, 1938, and 1939 by Ole Colbjørnsen, a Labour member of the Norwegian Storting (Parliament).

The motivation for the first nomination was written by women in the Norwegian branch of Friends of India, a network of associations in Europe and the US. However, the Nobel Committee’s adviser, Professor Jacob Worm-Müller, argued in his report that Gandhi, although “a good, noble and ascetic person”, was given to “sharp turns in his policies”, which made him both “a freedom fighter and a dictator, an idealist and a nationalist”.

Worm-Müller referred to critics who alleged Gandhi was not consistently pacifist, and doubted if his ideals were universal — his “struggle in South Africa was on behalf of the Indians only, and not of the blacks…”

In 1947, Gandhi was nominated by B G Kher, G V Mavalankar and G B Pant. Pandit Pant described him as the “the greatest living exponent of the moral order and the most effective champion of world peace today”.

This time, the Committee’s adviser, historian Jens Arup Seip, gave what the Nobel website describes as a “rather favourable, yet not explicitly supportive” report.

Committee Chairman Gunnar Jahn recorded that two members, Christian conservative Herman Smitt Ingebretsen. and Christian liberal Christian Oftedal, favoured Gandhi, but the other three — including Labour politician Martin Tranmæl and former Foreign Minister Birger Braadland who did not want to honour Gandhi in the middle of Partition and riots — did not. The Nobel went to The Quakers.

What about a posthumous consideration?

Gandhi was assassinated two days before the 1948 Peace nominations closed. There were six nominations on his behalf, including from the 1947 and 1946 Laureates, The Quakers and Emily Greene Balch. Seip wrote that given the numbers of people on whose attitudes Gandhi had left his mark, he “can only be compared to the founders of religions”.

The Nobel Foundation’s statutes did allow a posthumous award under certain circumstances. But Gandhi did not belong to an organisation and had not left a will, so it was unclear who would receive the prize money.

The Committee’s lawyer, Ole Torleif Røed, sought the opinion of prize-awarding institutions, and was advised against a posthumous award. Eventually, the Committee said “there was no suitable living candidate” that year. Chairman Jahn recorded that Oftedal dissented on this.

The big picture on the exclusion of the Mahatma then, is as follows:

* Up to 1960, when anti-apartheid activist Albert John Lutuli was honoured, the Peace Nobel went almost exclusively to Europeans and Americans. According to the Nobel website, Gandhi was a ‘different’ man — not a real politician or proponent of international law, not a humanitarian relief worker, not an organiser of global peace congresses.

* The Committee’s archives do not suggest that a possible adverse British reaction to an award to Gandhi was ever taken into account.

* In 1947, a majority in the Committee had doubts about the consistency of Gandhi’s pacifism, triggered by a misleading news report that quoted him as saying that “if there was no other way of securing justice from Pakistan… the Indian Union Government would have to go to war against it”, and “Muslims whose loyalty was with Pakistan should not stay in the Indian Union”.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05