- India

- International

‘Tomb of Sand’, Geetanjali Shree and Daisy Rockwell’s International Booker Prize-winning novel, traces a storied past and the futility of borders

The transformative journey of its octogenarian protagonist is told through a polyphony of voices, deftly translated by Rockwell for a global audience

The winner of the 2022 International Booker Prize is ‘Tomb of Sand’ by Geetanjali Shree, translated from Hindi to English by Daisy Rockwell. (Twitter/@TheBookerPrizes)

The winner of the 2022 International Booker Prize is ‘Tomb of Sand’ by Geetanjali Shree, translated from Hindi to English by Daisy Rockwell. (Twitter/@TheBookerPrizes)On the very first page of Tomb of Sand, the translation of Geetanjali Shree’s Ret Samadhi by Daisy Rockwell that won this year’s International Booker Prize, Shree writes that the book is a story of two women and one death. But it isn’t merely that. It is a tale told across the vanishing leap of time, across borders, genders and relationships, across the insurmountable hopelessness that men generate and the sea of hope they populate. “Women are stories themselves,” writes Shree. As the novel progresses, the many storied lives of her female protagonists hold the universe of her novel together.

🚨 Limited Time Offer | Express Premium with ad-lite for just Rs 2/ day 👉🏽 Click here to subscribe 🚨

Critics have variously tried to classify the book into a genre. It belongs to the genre of Partition novels, they said. Yes, it does but no, it doesn’t. It belongs to the genre of romances. Yes, it does or maybe no, it doesn’t. It can be classified as a feminist novel, they said. Yes, surely it can, but no it can’t. Just like the sky — vast and borderless — its canvas stretches beyond genres. That’s the power of this book and its quintessential je ne sais quoi.

Eighty-year-old Ma is the protagonist of the novel. Well, even that may not be true, because protagonists are the stabilising force in a story. Ma destabilises the tale. She is the one who brings in chaos. Every page that she appears in is enthralling madness — a madness that makes you fall in love with her character, that gives so much stability to the story that you want the tale to never end, quite like the night of love which Shree creates almost at the end of the book, a night of ragas and memories.

Just like people in our lives, there are other characters, too, in the novel — the good, the bad, the beautiful, the ugly and most importantly, the undefinable ones. There’s Bade, the man of the house (strange that ‘Man Of The House’ can be abbreviated as MOTH, meaning ‘death’ in Hindi); there’s his wife, Bahu, and their two sons. Bahu and Bade refer to each other with ‘D’. It stood for Darling after their marriage, but (de) metamorphosed into Duffer as years went by. Then there is Ma’s daughter, Beti, the bohemian who challenges both MOTH and family traditions and who is the second woman in this tale. And, finally, there is Rosie bua, the undefinable one. She-He. Rosie-Raza. The character who brings Ma to life. She, too, adds madness to the tale. These characters from a wide stratum of society that Shree has populated the Tomb of Sand with, fuel the storyline and reflect her impeccable depiction of the chasm between caste and class.

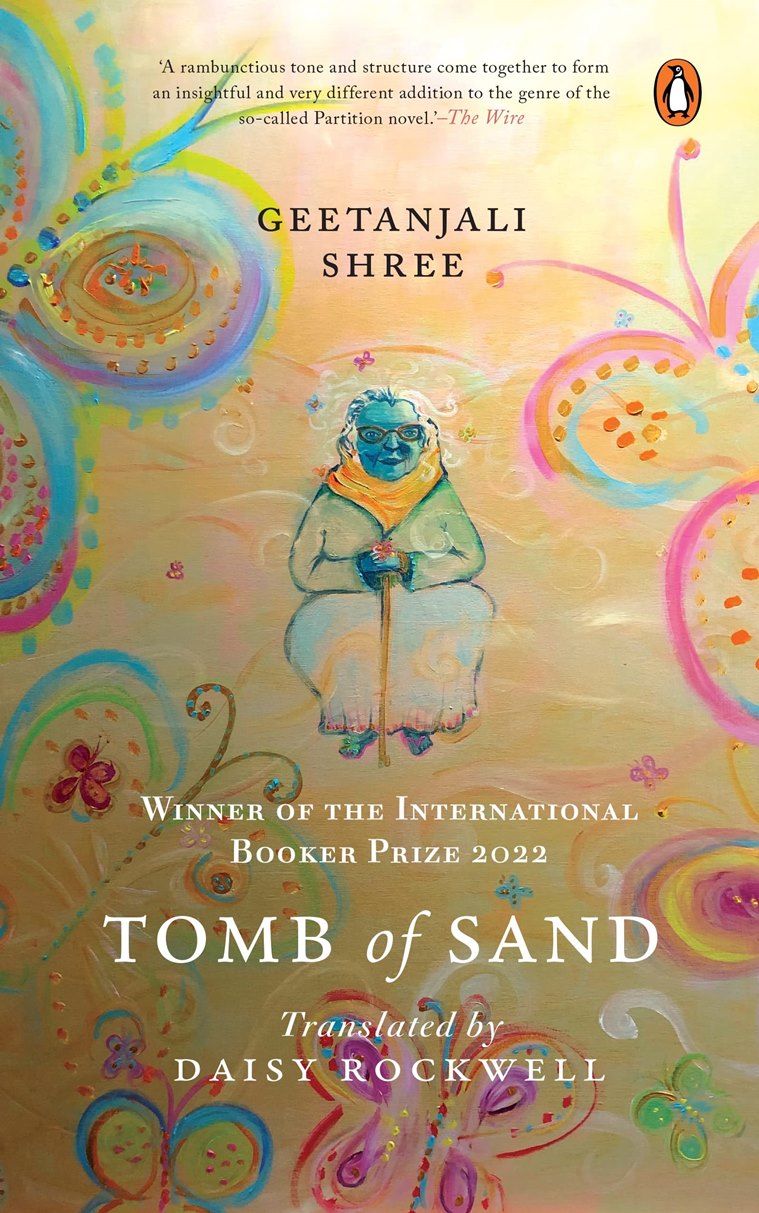

Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree; Translated into English by Daisy Rockwell; Penguin Random House; 696 pages; Rs 699 (Source: amazon.in)

Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree; Translated into English by Daisy Rockwell; Penguin Random House; 696 pages; Rs 699 (Source: amazon.in)

Ma is a perfect fictional representation of the vicissitudes and shades of life she lives. She has a bit of Ammu from Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things (1997), a touch of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Úrsula Iguarán from One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), a hint of Krishna Sobti’s Ammi from Aai Ladki (1991), and an air of Sethe from Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987). She makes you laugh gregariously and sob incessantly. She can love and hate with equal zest. She becomes a wall one moment and a door the very next, as much invisible as she’s visible. She’s the kind of character whom generations will love and relate to.

Ma subverts this story one last time when she decides to go to Pakistan. That’s the moment in the book when the reader is faced with the futility of a border. Shree exposes the ineptness of borders against the will of people in search of love and hope. She writes, “A border is a horizon. Where two worlds meet. And embrace. A border is love…”

Shree’s ability to describe the indescribable is the other hallmark of Tomb of Sand. She repeats what she did effectively in Mai (1993) and Humara Sheher Us Baras (1998), becoming in turn all those that many ignore — walls, doors, chrysanthemums, cane and even dust. She employs surrealism to propel the story. A man called Anwar appears on page 225 of the book, disappears and reappears again on page 584, but all this while, the reader keeps looking for him. He’s the silent charm of the book and just one example of Shree’s sheer mastery in making us wait in anticipation for a character who never utters a word and who cannot move.

It is in the moments of magic realism, a genre in which the book can fit in snugly, that the literary genius of Shree is revealed. The Solomon moments wherein Shree weaves the language of the crows and partridges into a beautiful tapestry of words act as the sutradharas in the tale, drawing us closer to the narrative. And then the moment where she collects the writers of Partition at the Wagah border — Khushwant Singh, Krishna Sobti, Saadat Hasan Manto, Intizar Hussain, Rahi Masoom Raza and others, all with their stories, characters and words, pierce the soul. What more would anyone want than Bishan Singh from “Toba Tek Singh” (1955) saddleless through the change of guard ceremony at the Wagah border?

If beautiful language enslaves one, translations set you free. This translation of Tomb of Sand by Daisy Rockwell sets Ret Samadhi free for a global audience. A good translation is like a revolution. It gives language, culture and identity a new perception and a new freedom. For Tomb of Sand, I can believe what Ngugi wa Thiong’o had said in Dreams in a Time of War (2010) — “Written words can also sing”.

Do I regret anything in the book? Yes, I do. I regret not reading it in 2018 when it was first published in Hindi. And most importantly, I regret being a man in the land of fabulous women like Ma, Beti and Rosie — women who are an antitheses to all the wisdom men offer them relentlessly. Tomb of Sand is a mausoleum to their hope and happiness.

In the Art of the Novel (1986), Milan Kundera says, “The stupidity of people comes from having an answer for everything. The wisdom of the novel comes from having a question for everything.” In Tomb of Sand Geetanjali Shree has a question for everything that we have in today’s broken world — hate, hopelessness, myth and identity. She effectively proves that in the age of disbelief, love continues to be a belief for some.

(Shah Alam Khan is professor, department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. Views are personal)

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05