- India

- International

Explained: The story of Rajiv Gandhi assassination convict A G Perarivalan, and his mother

A G Perarivalan was sentenced to death by a TADA court in 1998 in the Rajiv Gandhi Assassination case, and the sentence was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1999.

A G Perarivalan with his mother Arputham Ammal and others at a tea stall, on his way home following his release on bail from the Puzhal jail in Tamil Nadu’s Vellore town. (PTI Photo)

A G Perarivalan with his mother Arputham Ammal and others at a tea stall, on his way home following his release on bail from the Puzhal jail in Tamil Nadu’s Vellore town. (PTI Photo)

A G Perarivalan alias Arivu, 50, was 19 when he was arrested on June 11, 1991. He was accused of having bought two 9-volt ‘Golden Power’ battery cells for Sivarasan, the LTTE man who masterminded the conspiracy. The batteries were used in the bomb that killed Rajiv Gandhi on May 21 that year.

The case in the Supreme Court seeking remission for Perarivalan is one of the many legal battles he has waged from his cells in Vellore and Puzhal Central prisons in Tamil Nadu over the past three decades. On Wednesday (May 18), the SC ordered his release.

Many legal battles, incarceration of Perarivalan

Perarivalan was sentenced to death by a TADA court in 1998, and the sentence was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1999. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the Supreme Court on February 18, 2014, along with the death sentences awarded to other convicts in the case, Murugan and Santhan.

The ongoing case in the SC was part of a 2015 remission plea submitted by Perarivalan to the Tamil Nadu Governor, seeking release under Article 161 of the Constitution. He moved the Supreme Court after receiving no response.

He received parole for the first time in August 2017, to meet his ailing father, a Tamil poet and a retired school teacher.

The parole order said that he had completed the sentences awarded to him for various offences for which he had been convicted, and that he was now serving time in prison only under Section 302 (punishment for murder) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The order said it was open to the appropriate authority (the state government) to consider the case of the convict.

Hearing his plea on the delay in deciding his plea for remission, the SC had said in September 2018 that the Governor had the right to decide on his petition. Within days, the Tamil Nadu Cabinet, headed by then Chief Minister Edappadi K Palaniswami, had recommended the release of all the seven convicts in the case. But the Governor had chosen to sit on the Cabinet’s recommendation.

Perarivalan’s mother Arputham meets former Tamil Nadu chief minister late J Jayalalithaa in Chennai in February 2014. (Express Archive)

Perarivalan’s mother Arputham meets former Tamil Nadu chief minister late J Jayalalithaa in Chennai in February 2014. (Express Archive)

The Governor faced strong remarks from the Madras High Court in July 2020. The HC reminded the Governor that no time limit had been prescribed for the constitutional authority (Governor) to decide on such issues only “because of the faith and trust attached to the constitutional post”. The court added that “…If such authority fails to take a decision in a reasonable time, then the court will be constrained to interfere.”

In January 2021, the SC too expressed displeasure on the long delay on the part of the Governor, and warned that the court may be forced to take a decision. The government counsel promised that a decision would not be delayed further. But taking everyone to surprise, the Governor’s office forwarded the file to President Ram Nath Kovind for a decision in February 2021.

Senior jurists described the Governor’s action as “illegal”, and the SC raised questions on the move in multiple hearings after that. The matter continues to lie with Rashtrapati Bhavan.

In the meantime, the state government granted parole to Perarivalan on May 19, 2021. His parole was subsequently extended on “health grounds”. The Supreme Court granted him bail on March 9, 2022.

The charges against Perarivalan

“…Moreover, I bought two 9 volt battery cells (Golden Power) and gave them to Sivarasan. He used only these to make the bomb explode,” said Perarivalan’s confession statement taken under Section 15(1) of TADA, which played a key role in establishing his link with the assassins.

The TADA court’s verdict shows the confession was used to establish his knowledge and role in the assassination. But in multiple pleas before the Governor, the President and the courts since his conviction in 1999, Perarivalan consistently claimed innocence.

Giving legitimacy to Perarivalan’s claims, a 1981-batch IPS officer named V Thiagarajan revealed in 2013 that he had, in fact, altered the statement that was taken from Perarivalan while he was in custody under TADA. Thiagarajan revealed that Perarivalan had indeed admitted to having purchased the batteries, but he did not know the purpose.

“As an investigator, it put me in a dilemma. It wouldn’t have qualified as a confession statement without his admission of being part of the conspiracy. There I omitted a part of his statement and added my interpretation,” Thiagarajan said. An affidavit in this regard was also filed before the SC.

Four witnesses were examined by the TADA court regarding the 9 volt battery to corroborate Perarivalan’s confession statement. Of these four witnesses, three were forensic experts who gave expert opinions on the battery and the bomb. The fourth was an employee of a shop in Chennai that claimed to have sold the battery.

In a 2017 interview with The Indian Express, Justice K T Thomas, who headed the SC Bench that awarded the final order in the Rajiv Gandhi assissination case, said Perarivalan’s case had brought to the fore another aspect of the case that generated intense debate — using the confession of one accused against another.

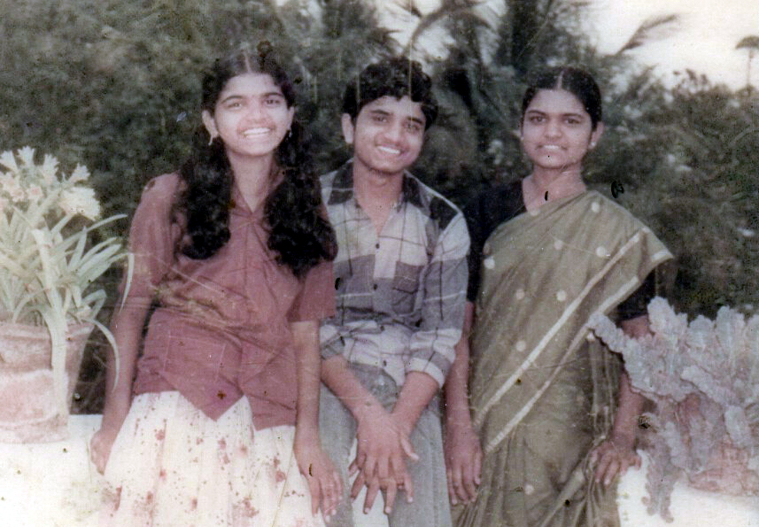

Perarivalan with his sisters Arulselvi (left) and Anbumani. (Express Archive)

Perarivalan with his sisters Arulselvi (left) and Anbumani. (Express Archive)

“Under the conventional Evidence Act, a confession can be used only as a corroborative piece of evidence. But the two other judges on my Bench did not agree, they insisted that we should use it as substantive evidence. To prevent the laying of such a wrong law, I called them to my home where we had several rounds of debates in which I tried to convince them. But the majority view in the judgment considered the confession statement as substantive evidence as it was under TADA (Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act). Later, many senior jurists called me to say that the majority order laid a wrong law in the case,” he said.

Jurists who stood for Perarivalan

Among the factors that sustained Perarivalan’s long battle was the determination and commitment of his mother, Arputham Ammal, who emerged as the face of an anti-death penalty movement, and the sympathy and empathy that he received from people from all walks of life.

“His soul is precious, his values noble, his jail life has not made him a criminal,” wrote the former SC judge, the late Justice V R Krishna Iyer, in 2006. Justice Krishna Iyer was in constant touch with Perarivalan until his death.

Justice Thomas, who had raised the question of ‘double jeopardy’ in 2013 in the case, which led to the SC order commuting the death sentences of three convicts in 2014, had pleaded with Sonia Gandhi to show magnanimity, and called the Governor’s decision to pass the buck to the President “unheard and unconstitutional”.

He cited the central government’s decision in 1964 to set free Gopal Godse, brother of Nathuram Godse, who was charged with conspiracy in the Mahatma Gandhi assassination case after 14 years of imprisonment.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05