- India

- International

Respect despite the discord: Subhas Chandra Bose’s relationship with Nehru, Gandhi and the Congress

The Bose-Gandhi rivalry is frequently understood as the biggest dichotomy of the Indian nationalist movement, its narrative often picked up by parties now to futher their own agenda.

Mahatma Gandhi with Subhash Chandra Bose. (Photo: Express Archive)

Mahatma Gandhi with Subhash Chandra Bose. (Photo: Express Archive)In public discourse and popular imagination Subhas Chandra Bose and the stalwarts of the Congress Party like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi are often seen at odds with each other. The Bose-Gandhi rivalry is frequently understood as the biggest dichotomy of the Indian nationalist movement, its narrative often picked up by parties now to futher their own agenda.

But was Bose really opposed to the Congress Party?

“Subhas Chandra Bose was a key member and a frontline leader of the Indian National Congress. He plunged into the anti-colonial movement under Gandhi’s leadership in 1921 and rose to be the president of the Congress in 1938 and 39,” reminded Sugato Bose, Professor of History at Harvard University. “There were certain differences of opinion with the Gandhian high command in 1939, but he remained true to the Congress ideal of freedom,” he added.

“Bose was a complex character,” explained historian Ramachandra Guha in an Indian Express Idea Exchange session. His complexity comes alive when one realises that despite his disagreement with the Congress leadership, when Bose took over the Indian National Army (INA), he constituted four regiments, three of which were named after Gandhi, Nehru and Maulana Azad. “He had profound respect for his colleagues,” said Guha. In 1943, while Gandhi was in jail, Bose on the former’s birthday gave a moving address over the Azad Hind Radio where he referred to Gandhi as ‘father of the nation’. As Guha noted, this was probably the first time this epithet was used for Gandhi, and soon it became ubiquitous.

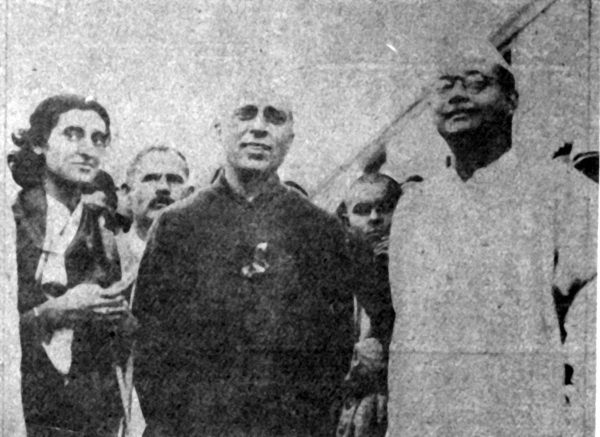

Indira Gandhi with her father Jawaharlal Nehru and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. (Photo: Express Archive)

Indira Gandhi with her father Jawaharlal Nehru and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. (Photo: Express Archive)

Joining the Indian National Congress

On July 16, 1921, Bose had returned to Bombay from London where he had gone on his father’s insistence to prepare for the Indian Civil Services examination. Despite qualifying for the services he had refused to take up the opportunity. In a letter to brother Sarat Bose, in September, 1920, he wrote: “It is not possible to serve one’s country in the best and fullest manner if one is chained on to the civil service” — as reproduced by historian Leonard Gordon in his book, ‘Brothers Against the Raj: A Biography of Indian Nationalist Leaders Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose’.

Such was Bose’s zeal to join the freedom struggle that on the very afternoon he arrived in India he went to meet Gandhi at Mani Bhawan. The main objective of his visit was to get from the leader of the campaign a clear idea of his plan of action. “I wanted to understand the Mahatma’s mind and purpose,” he had recollected later, as cited by historian Rudrangshu Mukherjee in his book, ‘Nehru and Bose: Parallel Lives’ (2014).

Mukherjee in his book narrated how Bose wanted to “know how the different aspects of the movement were going to culminate in the non-payment of taxes, the last stage of the campaign.” Secondly, he wanted to know how the non-payment of taxes would eventually force the British to leave and thirdly how Gandhi could promise Swaraj in one year. Bose was convinced by Gandhi’s response to the first question, but was rather unimpressed by his answers to the other two. “It appeared to him that for Gandhi, swaraj within one year was a question of faith. Gandhi left Subhas ‘depressed and disappointed’. Gandhi had failed to cast a spell on him,” wrote Mukherjee.

Mukherjee compared Bose’s relationship with Gandhi to that of Nehru, both leaders being of the same age of similar political leanings and often finding themselves frustrated by Gandhi’s commitment to non-violence. However, while Nehru was starry-eyed in his reverence for Gandhi, Bose though immensely respectful of Gandhi, found his political strategies to be ambiguous.

On Gandhi’s advice Bose moved to Calcutta, where he worked closely with the lawyer and Congress leader C R Das. Bose found Das to be inspirational in his leadership qualities. He was immersed in Congress work under his astute guidance. He was given the responsibility for publicity of the Bengal province Congress Committee and was appointed principal of the National College. He also began writing for the nationalist cause during this period. This was also the period when the non-cooperation movement began and Bose was thoroughly involved in it, directing and organising Congress volunteers in Calcutta.

In February 1922, Gandhi had unilaterally called off the non-cooperation movement on account of the outbreak of violence at Chauri Chaura. Both Bose and Nehru had been in prison at that time and both expressed disappointment and anger in knowing that the movement they had worked so hard for, had been forced to wind up.

Much has been made of the rivalry between Nehru and Bose, but on issues like Chauri Chaura and several others, they were in fact very closely aligned. Both were left-leaning radical men, unswerving in their commitment to ‘purna swaraj’ and to the forming of a socialist state in independent India. In their dedication to independence, they both were often at loggerheads with those within the Congress who were more attracted to the idea of holding office in the provincial governments.

“Gandhi’s withdrawal of both the non-cooperation and the civil disobedience movements exasperated the two radical young men. They were bewildered by his emphasis, at this critical phase of the national movement, on social uplift and spinning. They yearned to go forth into battle to confront British rule while Gandhi throughout the 1930s was reluctant to call a mass movement on the grounds that neither the Congress nor the people were prepared for it,” wrote Mukherjee. Despite their shared frustrations, they both reacted to the situation differently. Nehru yielded while Bose rebelled.

The political rivalry between Bose and Nehru developed only from the later 1930s, and were a product of their differing attitudes towards Gandhi and the nationalist movement as well as their opposing views towards Fascism and the Second World War.

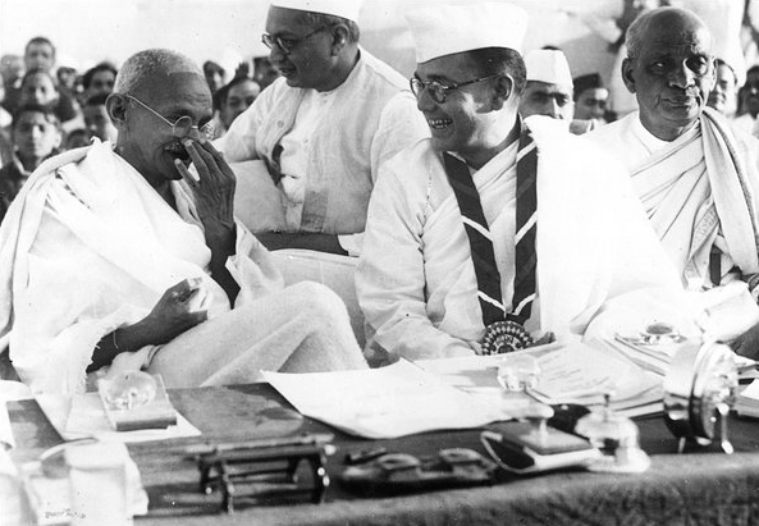

Mahatma Gandhi at the Indian National Congress annual meeting in Haripura in 1938. Congress President Subhas Chandra Bose is wearing the ribbon, seated behind him is Dr Rajendra Prasad, and to the right of Bose is Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Mahatma Gandhi at the Indian National Congress annual meeting in Haripura in 1938. Congress President Subhas Chandra Bose is wearing the ribbon, seated behind him is Dr Rajendra Prasad, and to the right of Bose is Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

As Congress president

In February 1938 Bose had taken over as president of the Congress and the next two years would be defining in creating his political profile as a Congressman and in drawing the rift with Gandhi and Nehru. At the Haripura session of the Congress, Bose made his presidential address, which is known to be the lengthiest and most important speech he ever made to the party. He made it clear that he stood for unqualified Swaraj.

However, it needs to be noted that nowhere in the speech did Bose suggest any criticism or deviation from Gandhi’s methods. He said, as cited in Mukherjee’s book, “I believe more than ever that the methods should be Satyagraha or non-violent non-cooperation in the widest sense of the term, including civil disobedience. It would not be correct to call our method passive resistance. Satyagraha, as I understand it, is not merely passive resistance but active resistance as well though that activity must be of a non-violent character.”

As president of the Congress, his first disagreement with Gandhi happened in December 1938 when Bose was eager to form a coalition government in Bengal along with the Krishak Praja Party. Gandhi’s letter to Bose sternly dictating him to stay away from including Congress in the Bengal ministry came as a rude shock to the latter. Bose was under the impression that Gandhi was on the same page as him with regards to the Bengal ministry.

The seeds of discord with Gandhi had been sown with this disagreement. In a curt reply to Gandhi, Bose madeit clear that if he did not change his decision he would have to carefully consider his position.

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi releasing the first volume of collected works of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, edited by Dr Sisir K Bose, in New Delhi on November 28, 1980. (Photo: Express Archive)

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi releasing the first volume of collected works of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, edited by Dr Sisir K Bose, in New Delhi on November 28, 1980. (Photo: Express Archive)

The following year, Bose was hopeful for re-election as Congress president. A second term was very rare and Gandhi was pretty much against the idea of re-electing Bose. The latter found support from the younger and left leaning members of the Congress and also from the literary giant Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore had personally written to Gandhi requesting a second term for Bose. “The prospect of a prolonged agony of humiliation for my province compels me at last to appeal to you with an earnest request that you may use your influence to offer Subhas (Bose) another chance for presidentship in the Congress,” he wrote as cited in Guha’s book, ‘Gandhi: The years that changed the world: 1914-1948’. Tagore was aware that Bose was regarded, not just by Gandhi, as hot-headed and temperamental, but assured in his letter to Gandhi that he would help Bose from his own vantage ground if he so desired.

Generally and ever since Gandhi’s emergence as the party’s preeminent leader, the president would be chosen by consensus. With Gandhi and Bose both sticking to their grounds on the matter of re-election, an election had to be organised by the All India Congress Committee (AICC). Bose won comfortably, getting the support of 1,580 AICC members, about 200 more than Pattabhi Sitaramayya, who was the preferred candidate of Gandhi.

Gandhi was at Bardoli when he heard of Bose’s re-election. In his statement he wrote: “I must confess that from the very beginning I was decidedly against his re-election for reasons which I need not go into. I do not subscribe to the facts or the arguments in his manifestos. I think that his references to his colleagues were unjustified and unworthy. Nevertheless, I am glad of his victory. And since I was instrumental in inducing Dr. Pattabhi not to withdraw his name as a candidate when Maulana Saheb withdrew, the defeat is more mine than his.”

Bose was aggrieved to know that Gandhi saw this as a ‘personal defeat’. Despite the differences he saw Gandhi with utmost respect as was evident from the responding statement he issued: “It will always be my aim and object to try and win his confidence for the simple reason that it will be a tragic thing for me if I succeed in winning the confidence of other people but fail to win the confidence of India’s greatest man.”

Even if Gandhi was open to compromise, his supporters were not. In response to Bose’s re-election several members of the Congress Working Committee resigned including Vallabhbhai Patel and Rajendra Prasad. Among the detractors, no one was more opposed to Bose than Patel.

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose reviewing the troops of Azad Hind Fauj in 1940s. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose reviewing the troops of Azad Hind Fauj in 1940s. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Patel had an old rivalry with Bose, which was both personal and political. Their relationship had deteriorated rapidly with the death of Patel’s elder brother Vithalbhai in 1933. Bose had been very close to Vithalbhai and had nursed him during his last days. In his will, Vithalbhai had left a substantial portion of his property to Bose. Vallabhbhai had cast aspersions on the authenticity of the will and a long legal battle had followed culminating in the victory of Patel.

But the family history aside, Patel was also staunchly against Bose’s strategy of militant socialism. “Bose wanted to bring the peasants and workers into the nationalist movement, while Patel believed in class conciliation and wanted to work with the landlords and the industrialists,” said Sugata Bose.

On several occasions in the following months, Bose wrote to Gandhi, urging him to take a more adversarial stance towards the British Raj and help in the reconciliation of the party that had been split apart ever since his re-election. Gandhi remained unmoved in his position. In a letter to Bose written in March 1939, he said: “I smell violence in the air I breathe. But the violence has put on a subtle form. Our mutual distrust is a bad form of violence. The widening gulf points to the same thing.”

On April 29, 1939 Bose resigned from his post as president of the Congress Party. In a statement to the press, he mentioned the efforts he had made to find a common ground with Gandhi. “These having failed, he felt his presidency may be a sort of obstacle or handicap in the path of the Congress as it sought to reconcile its two wings,” wrote Guha in his book.

Life after leaving Congress

In September 1939 German tanks invaded Poland, marking the beginning of the Second World War. The war was to have a most significant impact in the history of modern India. The difference in the attitude towards the war would be the final straw in the embittering relationship between Bose and the Congress leadership, particularly Nehru.

Bose was a special invitee in the three-day meeting of the Congress Working Committee from September 9 to decide India’s position on the war. For Bose, the war served as a golden opportunity for India to launch a civil disobedience movement in order to win independence. The resolution put forward by the CWC on the other hand reflected the views of Nehru who had drafted it. The resolution asked the British government to clarify its position on the war with regard to imperialism and democracy and till such time postponed the decision of the Congress on the matter. For Bose the stance taken by the resolution was completely unacceptable. He suggested, as noted by Mukherjee in his book, that the resolution was “long-winded” amounting to nothing but mere words.

Nehru had nothing but hatred towards Fascism and Nazism and sought for some concessions from the British government to fight Mussolini and Hitler. Bose was critical of the position of compromise taken by the Congress. He wrote in the strongest language possible that the resolution of the CWC read as “we shall continue to lick the feet of the British government even though we have been kicked by them.” Bose’s consistent outbursts with regard to the Congress’ position angered Nehru. In a letter to V K Krishna Menon he wrote, “Subhas Bose is going to pieces and has definitely ranged himself against the Congress.”

A newly elect president of the Indian National Congress, Subhas Chandra Bose, arrives at Calcutta’s Dum Dum aerodrome after an eventful European tour.

A newly elect president of the Indian National Congress, Subhas Chandra Bose, arrives at Calcutta’s Dum Dum aerodrome after an eventful European tour.

In his exasperation, Bose was seeking an alternative leadership to that of the Congress. In March 1940 he organised the All India Anti Compromise Conference in Ramgarh. He urged his audience to act while before it was too late. “He presented the examples of Lenin and Mussolini as leaders who seized the moment in history and provided decisive leadership to their countries. He ended the speech with ‘Inquilab zindabad’, a sign off that would soon become his trademark,” wrote Mukherjee.

Having failed to convince the Congress to go into civil disobedience, Bose organised mass protests in Calcutta for the removal of the Holwell monument that stood in Dalhousie Square as a memorial to those who died in the Black Hole of Calcutta. He was arrested by the British government for the protests, but was released soon after he went into a seven-day hunger strike.

Bose’s arrest and the subsequent release set the scene for him to escape to Germany via Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. When Bose sought the support of the Nazi governement in Germany, he found himself ideologically at the farthest end to Nehru’s views on the matter. Writing about Bose’s position on Nazism Mukherjee said, “Subhas had from his youth a fascination for things military, and this may be one factor that attracted him to militaristic regimes.”

The so-called ashes of Netaji are kept at the Renkoji Temple in Tokyo. (Photo: Shyamlal Yadav)

The so-called ashes of Netaji are kept at the Renkoji Temple in Tokyo. (Photo: Shyamlal Yadav)

Despite the many differences, political experts have maintained that Nehru and Bose shared a close personal relationship, as was evident in the way Bose named the brigades in the INA. “If you look at the period when Netaji was in Europe, he was the one who accompanied Kamala Nehru to the sanatorium while Nehru was in India. He was also present at Kamala Nehru’s funeral,” said Sugato Bose, also grand-nephew of Bose. “Nehru would also always be a guest to Sarat Bose, my grandfather, whenever he visited Calcutta.”

It is also worth noting that at the end of the Second World War, Nehru put on his barrister’s gown and joined the defense team for the INA prisoners at the time of the Red Fort trials. In the several speeches of Nehru after Bose’s death, the former referred to Netaji in the most affectionate way. In January 1946, for instance, speaking on Bose’s birth anniversary, he said, “Subhas Bose and I were co-workers in the struggle for freedom for 25 years… Our relations with each other were marked by great affection. I used to treat him as my younger brother. It is an open secret that at times there were differences between us on political questions. But I never for a moment doubted that he was a brave soldier in the struggle for freedom” — as quoted in Mukherjee’s book.

Sugata Bose said that “in August 1947, in his first speech from the ramparts of the Red Fort, Nehru mentioned only two people by name and they were Gandhi and Bose. It was quite a warm reference.”

Bose on his part too had on several occasions displayed his reverence and affection for the Congress leadership. In his address from Bangkok on the Azad Hind Radio in October 1943, he reminded his Indian listeners that this was the birthday of “their greatest leader, Mahatma Gandhi”. In his address he reiterated Gandhi’s contribution to the freedom movement. “‘The service that Mahatma Gandhi has rendered to India and to the cause of India’s freedom,’” said Bose, ‘is so unique and unparalleled that his name will be written in letters of gold in our national history for all time,’” wrote Guha. “The task that Mahatma Gandhi began has, therefore, to be completed by his countrymen- at home and abroad,” said Bose as he ended his speech.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05